Oh, hey. I kinda screwed up.

I had been thinking about featuring a poem or two in this space. First, of course, so I can show off my vast knowledge of poetry. (Heh.) But also to share some of my faves with all of you, my loyal readers. (You two know who you are.)

This thinking had started somewhat earlier in the year, but then really coalesced when I had done the Memorial Day entry and mentioned Owen’s Dulce et Decorum Est. I hadn’t included that poem then, saying it belonged for another day. Which was true. But also I thought that if I started throwing out poems, I should start with the one that I somewhat consider my first favorite poem, the first poem that really made me dig deeper and actually appreciate poetry.

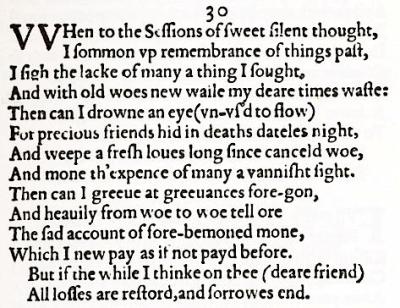

But then one day, without thinking, in haste maybe, desperate for a blog entry, I just kinda coughed up Shakespeare Sonnet #30. Sure, it’s a favorite, it’s great and all, but it’s not the one I had decided to be the first poem featured here. That great honor was supposed to go to Yeats’s An Irish Airman Foresees His Death.

I KNOW that I shall meet my fate

Somewhere among the clouds above;

Those that I fight I do not hate

Those that I guard I do not love;

My country is Kiltartan Cross,

My countrymen Kiltartan’s poor,

No likely end could bring them loss

Or leave them happier than before.

Nor law, nor duty bade me fight,

Nor public man, nor cheering crowds,

A lonely impulse of delight

Drove to this tumult in the clouds;

I balanced all, brought all to mind,

The years to come seemed waste of breath,

A waste of breath the years behind

In balance with this life, this death.

I first encountered this poem watching a movie, actually. My all-time favorite stripper Christina had recommended this movie Memphis Belle to me. I don’t remember if I then rented it or just found it on cable somewhere. I think maybe I just happened to catch it on cable. I do remember that I watched it at my mother’s house, upstairs in the loft, on that TV up there. Must have been 1996 or 1997.

The eponymous Memphis Belle is an aircraft in World War Two, a bomber. Maybe a B-17 or B-29, doesn’t really matter. The ensemble cast are crewmen on the plane, and one of them is Eric Stoltz. He plays like this sensitive guy, and the others are always teasing him about how he’s always writing stuff down in his notebook. At one point somebody snatches it away from him and starts reading it, and I think Eric Stoltz snatches it back. But anyway they make him read aloud from it. And he reads this poem.

And he reads it as if it were something that he himself wrote. But later in the movie he’s wounded, and unconscious, and then after that when he comes back to consciousness, even just as he’s coming back around, he’s saying, “I didn’t write that. W.B. Yeats wrote that.”

But I had liked it so much when he had read it, aloud. And it made so much sense in context, in the context of his situation. (Now I can look back and think that maybe it’s a little too apropos, but whatever, right?) And it was lovely and sad. And then when you read it on the page, you see that it’s nice and traditional, good rhyme and meter. So, again, like the Shakespeare sonnet, it’s satisfying in content in a traditional form. That sums up a lot of my poetry sensibility right there.

So, Eric Stoltz reads this lovely & poignant poem, and then later announces that it’s actually from Yeats. And I know that I’ve heard of Yeats, right? I remember getting Yeats and Keats mixed up when I was in high school, or maybe later. But I’ve at least heard of this Yeats guy. Like maybe he wrote that Ozymandias poem, or maybe that was Keats. (It’s actually Shelley.) But I know Yeats totally wrote that Second Coming poem. You know, “What rough beast … slouching toward Bethlehem to be born,” that one? In Stephen King’s The Stand, one character refers to this poem, and mispronounces Yeats’s name, using the long “e” and calling him Yeets.

But anyway, I had grabbed my old copy of The Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry, which I had owned for years but hardly glanced at ever, except maybe for trying to read Gerard Manley Hopkins one time, when my then-girlfriend Cathy had gotten into him. And the Norton had like fifty pages of Yeats, including The Second Coming and An Irish Airman Foresees His Death. And so I started reading some Yeats.

And some of them I liked and some of them I didn’t. But some of them I liked(!), which was great. And new to me as well. I had thought poetry to be pretty useless, like in high school, declaring that if somebody decided to write something in secret code, why the hell should I bother to try to figure it out. I even once wrote a poem, snarkily called Emily Dickinson Eats Worms, for a community college class. But then here I was, older, in my early thirties, not so full of myself now, with nothing to fear or prove, just reading and enjoying. I wasn’t being forced to read it either. Maybe that was part of it too. But whatever, here I had this amazingly great book of poetry, with annotations and explanations and short biographical sketches to fill in what otherwise I couldn’t figure out for myself.

And this particular poem, Irish Airman, I really like for a lot of reasons. First, as I said, I first heard it read aloud. And in that reading, I didn’t especially notice the rhyme or meter. It just sounded beautifully sad. But then looking at it, it does have a quite traditional scheme. And I love the contrast of the two lines about love and hate, that sort of bewilderment, that understanding but not understanding of where he is and why & whom he’s fighting for and against. I love of course his declaration of solidarity for Ireland, although he fights for England. And even more his declaration of solidarity for the poor of his county. And finally that weariness, that sadness, where the years behind and the years ahead are all even just a waste of breath.

Although it was featured in this Word War Two movie, it’s actually about a pilot in World War One, and he did actually die. Yeats wrote it for a friend, whose son is the airman in the poem. He did die.

It’s similar, the poem, to another poem, High Flight, by John Gillespie Magee. Contrast “this tumult in the clouds” in Yeats to Magee’s “tumbling mirth of sun-split clouds.” Except High Flight to me is really treacly, while Irish Airman is not. Not nearly so much, anyway. And the airman in Yeats is at least cognizant of why he flies and fights, and how unimportant he himself is in the scheme of things, whereas in Magee the pilot is all too self-absorbed, telling us how he has done things that we have never even dreamed of doing. And worst of all, Magee’s pilot declares that he has “touched the face of God.”

Number one, ew, as in it’s a bit gauche and grandiose, even for poetic metaphor. And but then number two, have you now, really? I’d figure the dead pilot of Yeats is a lot closer to God than Magee’s obnoxious braggart.

But, then, sadly, Magee did in fact die, at the tender age of nineteen, in a mid-air collision during a flight. Yeats lived to a ripe old age.

Finally, there’s one other little tidbit, regarding my love for Yeats. Having mentioned Wilfred Owen more than once now, you know that I’m a huge fan of the War Poets. But Yeats himself wasn’t, a fan, actually. Of Rupert Brooke’s poetic talent, Yeats once said that Brooke was “the handsomest young man in England.”